Insects with Impact

How Swan Valley Connections Can Help You Manage Bark Beetles for Healthy Forests

By Rob Rich

February 12. 2019

Winter is typically a quiet time of year, but come February, the phone at Swan Valley Connections (SVC) starts ringing. “Yes, the date is still April 15,” I can hear Leanna say down the hall. Leanna may be our longtime Office Manager, but everyone in earshot knows she’s not talking about tax day. She’s talking about another kind of deadline, determined by the time when Douglas-fir beetles take flight.

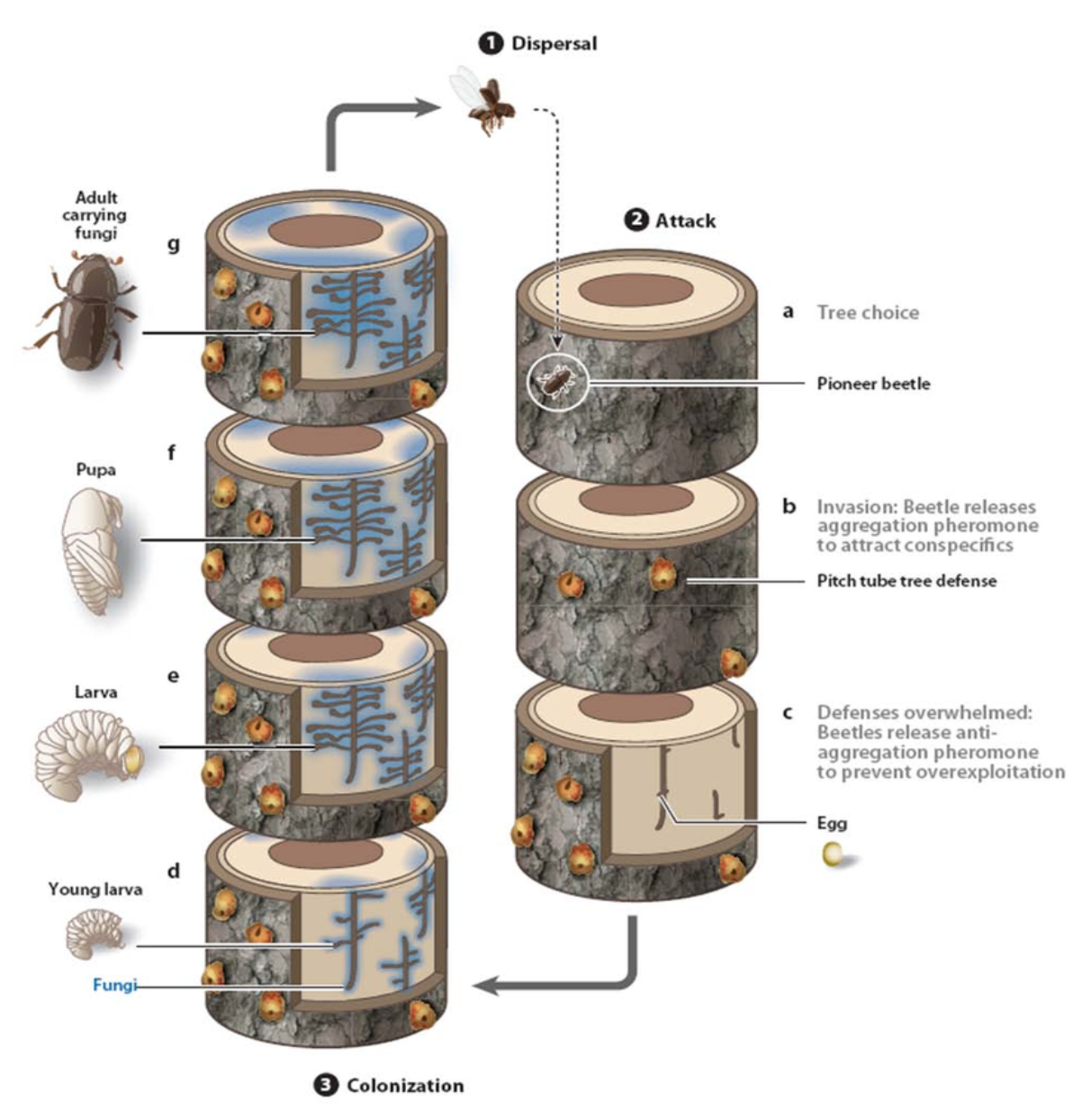

Bark beetles typically overwinter as larvae just below the bark of trees. Air temperatures define their emergence as adults, with Douglas-fir beetles typically beginning to fly around April 15, and mountain pine beetles between June 15 and July 1. Photo Credit: James Woodcock – Billings Gazette

The Douglas fir beetle (Dendroctonus psuedotsugae) (top) carves fan-like “galleries” from a central line underneath bark (left). The mountain pine beetle carves wider, more erratic galleries without a central line (right). Photo Credit: United States Forest Service.

Douglas-fir beetles, along with the mountain pine beetles, are creatures we love to hate. With a shared genus name that means “tree destroyer” (Dendro = tree, tonus = destroyer), it may not be surprising that many associate these insects with words like “nuisance” or “pest.” But unlike exotic invasive species such as zebra mussels or knapweed, these bark beetles are native to northwest Montana. Healthy forests require standing dead trees, or snags, and beetle-killed firs and pines have played key roles in diversifying and restoring landscapes for millennia. Woodpeckers, drawn to the beetle-feast, whittle cavities that later house bluebirds and other cavity nesters. Flowers and berries grow in the pockets of sun where the tree’s shade had been, and goshawks, deer, and bears find food in the renewed habitat, too.

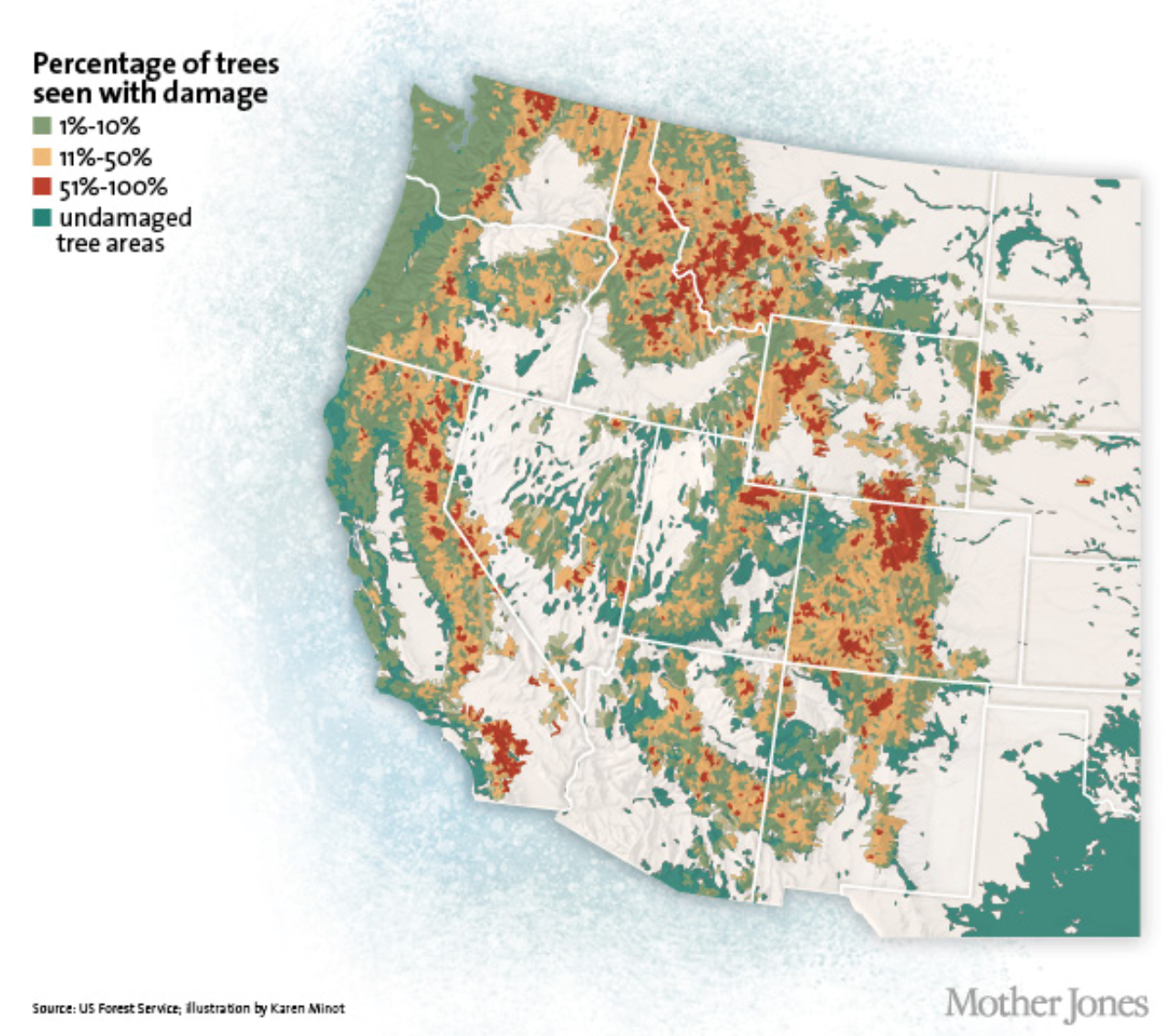

And yet, our forests today are stressed. Decades of fire suppression, periodic drought, and a rapidly warming climate have spurred beetle outbreaks the Intermountain West has never seen before. Bark beetles survive by consuming the living tissues that channel sugars through trees, called the phloem. If not checked by cold winters, woodpeckers, or tubes of sticky pitch exuding from under the bark ̶ a tree’s natural defenses ̶ mass aggregations of beetles can eat enough phloem to girdle and kill the tree. Beetles thrive by exploiting their hosts’ weaknesses and as climate-driven stressors on our trees mount, exploding beetle populations cast deadened waves of red and gray over the forest canopy. In a recent 2017 survey, Montana’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation reported that six million acres of our state’s forest have succumbed to mountain pine beetle outbreaks.

Image Credit: American Forests

Bark beetles have impacted wide swaths of the Intermountain West. Douglas-fir and mountain pine beetles typically colonize and kill large diameter, mature Douglas-fir, ponderosa pine, and lodgepole pine, trees landowners are often most keen to protect. They can also affect whitebark pine, a threatened species of our mountains.

University of Montana entomologist Diana Six is an expert on bark beetles and their unique co-evolution with blue-stained fungus. She explores the finest details of the beetle’s life cycle alongside the genetics of resistant trees to understand how our forests can be more resilient in a changing climate. Image Credit: Six and Wingfield, 2011.

The good news is that only 37,000 acres were counted as newly consumed by mountain pine beetles in 2017, a decline connected to the beetles’ depletion of single-age, single-species stands of lodgepole pine, which are highly susceptible to outbreak. These outcomes suggest that healing forests and buffering beetles requires an approach that values diversity, which is what SVC aims to foster with its “bubble cap” program. Unlike broadcast herbicide spraying or extensive removal of snags with high value for wildlife, each palm-sized bubble cap releases a beetle repellent that minimizes harm to the tree and its community. Once tacked to a tree, the bubble cap passively diffuses a chemical which mimics the pheromones released by the beetles themselves. This chemo-communication is effectively a “no vacancy” signal, triggering the beetles to move along to fresh territory.

That’s why, sometime between now and when the air temperatures say the beetles will fly, Leanna wants to hear from you. By placing one large bulk order for hundreds of landowners, she can reduce the unit cost and provide convenient pick-up or installation options that work for you. Leanna is especially eager to hook you up with our Conservation & Stewardship Associate, Mike Mayernik, who can walk you through the steps to prevent beetle outbreaks and protect forest health in a free site visit. Mike can not only help you identify the species and vulnerabilities of trees in your forest, but he can also help you discern if beetles are present and where solutions can be found. The beetle repellents we use are certified by the EPA as non-toxic to humans and other animals, and as a licensed dealer and applicator, Mike can also install your bubble caps safely for a small fee. Together, we can move towards balance with beetles, and a positive impact on our forests’ future.

Mike looks forward to protecting healthy forests with you! Photo Credit: Andrea DiNino